Table of Contents

I. Introduction

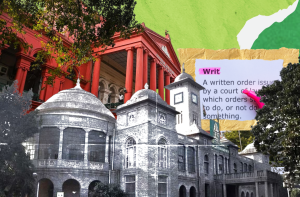

When two statutes with strong and overlapping powers apply to the same situation, a conflict of authority is inevitable. This is exactly what happens when a company enters the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC), while the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) simultaneously initiates its own enforcement actions.

Under CIRP, the Committee of Creditors (CoC) and the Insolvency Professional (IP) assume control over the corporate debtor’s property, which must be preserved to maximise value for all creditors.1 To enable this, Section 14 of the IBC imposes a moratorium on any recovery or enforcement proceedings against the company.2

SEBI, however, exercises regulatory powers to protect investors and market integrity. In cases involving securities fraud or unlawful fund-raising, SEBI may attach properties of promoters or the corporate entity to secure penalties or restitution for affected investors.3 These actions often continue even when the company is already undergoing insolvency.

This inevitable clash becomes sharper because both statutes contain overriding clauses: Section 238 of the IBC states that it prevails over any conflicting laws,4 while Section 28A(3) of the SEBI Act grants SEBI priority in recovering its dues notwithstanding anything inconsistent in other laws.5 This raises the critical question: when insolvency law demands asset preservation, and securities law demands asset attachment, which legal mandate should take precedence?

The first half of the blog will examine the lack of clarity on this issue by tracing landmark judgments as well as discussing the two latest cases in this matter i.e HBN Dairies & Allied Ltd6 (HBN Dairies case) and National Spot Exchange Ltd. v. Union of India & Ors.7(NSEL case). The second half of the blog will consider the economic implications for SEBI if the IBC takes precedence over the SEBI Act during the moratorium period.