Table of Contents

- I. Abstract

- II. Keywords

- III. Introduction

- IV. Why does all this matter?

- V. What the Numbers Reveal About the Performance

- VI. Rising Backlogs and Administrative Bottlenecks

- VII. Structural and Governance Fault Lines

- VIII. Reform: Capacity and Infrastructure

- IX. Strengthening Procedural Fairness

- X. Institutional Independence

- XI. Conclusion

I. Abstract

The Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT) system, introduced under the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 (RDDBFI Act), was seen as India’s institutional answer to the inefficiency of the civil courts in handling financial disputes. Three decades later, it stands at the crossroads of efficiency and equity. The whole structure is burdened with delays, deficits and low credibility. This blog argues for a paradigm shift from a bylane of recovery-centric approach to a debt justice approach that merges speed, fairness and transparency to strengthen its structure. Such a shift is important not only to restore the confidence of creditors and debtors, both, but also to ensure that India’s financial jurisprudence remains aligned with its macroeconomic stability and social equity.

II. Keywords

Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs), Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 (RDDBFI Act), Financial disputes, Debt, Recovery, Creditors, Debtors and Financial jurisprudence

DRAFT

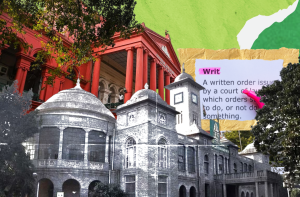

III. Introduction: Why DRTs Became Necessary

The economic reforms in the early 1990s unleashed a flood of new financial opportunities and new risks. Rising non-performing assets (NPAs) soon highlighted the limitations of civil courts in handling complex financial disputes. Although the idea of specialised tribunals for debt recovery was initially proposed by the Tiwari Committee (1981), it was the Narasimham Committee Report that strongly recommended their establishment. Acting on it, Parliament enacted the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 (now the Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act), establishing the Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) and Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunals (DRATs)1. These tribunals were designed to function as specialised quasi-judicial bodies adhering to statutory timelines, with the benefit of domain expertise and with minimal procedural rigour. The aim was to protect the financial system from paralysis. However, the reality is seemingly different. By 2025, there are more than 2.15 lakh cases pending in this tribunal nationwide2, and the statutory 180-day disposal window remains more aspirational than real. According to the Ministry of Finance, there are currently 39 DRTs and five DRATs functioning across the country, with jurisdiction distributed zone-wise.3 The question, therefore, is not merely about improving procedural efficiency within the DRT framework, but about reexamining its performance and reform trajectory through the lens of debt justice, to determine whether it functions as a truly balanced adjudicatory system rather than merely a recovery-centric enforcement mechanism. Debt justice, in this context, means more than the mechanical enforcement of loan contracts, referring to a just system that is efficient without being coercive and fair without being indefinitely delayed. In practice, this means designing a recovery framework that balances speed with procedural fairness and institutional accountability, so that enforcement outcomes remain credible, proportionate and trusted by all stakeholders.