Introduction

In our previous discussion, we delved into the imperative for a comprehensive national litigation policy (hereinafter NLP) and explored the consequences of its non-implementation in the routine litigation processes of the government. The blog post also sheds light on the existence of different litigation policies at the state level which are often termed State Litigation Policies (hereinafter SLPs). As part of our continuing analysis of government litigation, this post aims to scrutinize the working of litigation policies at the state level, and on the issue of deficiency in data.

Data at the state level

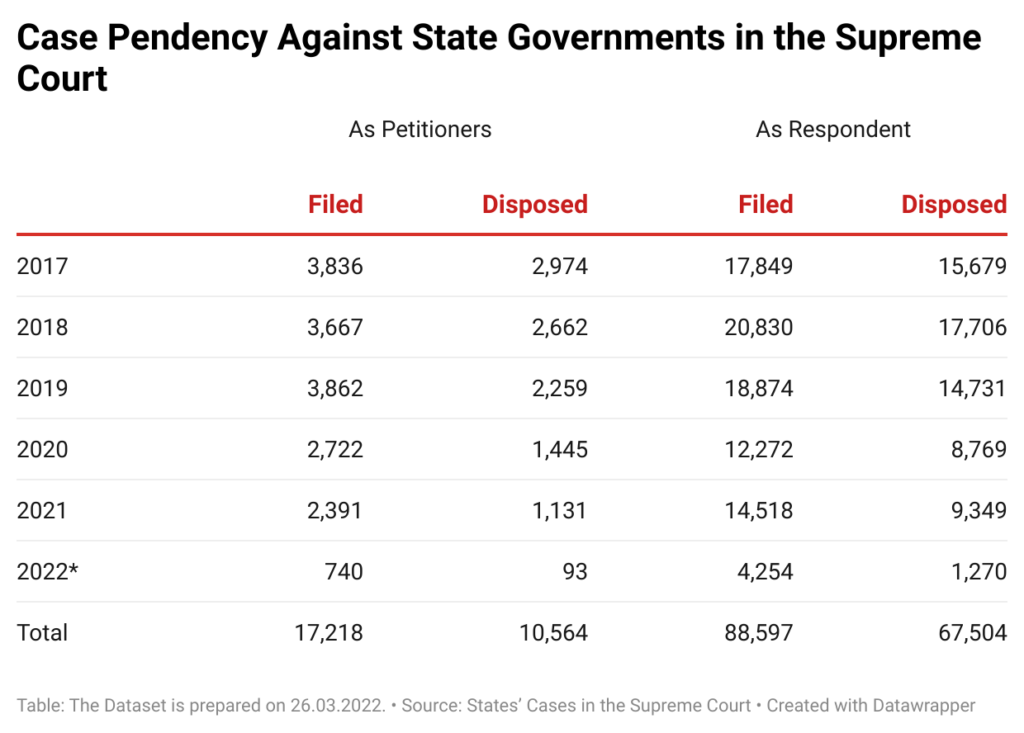

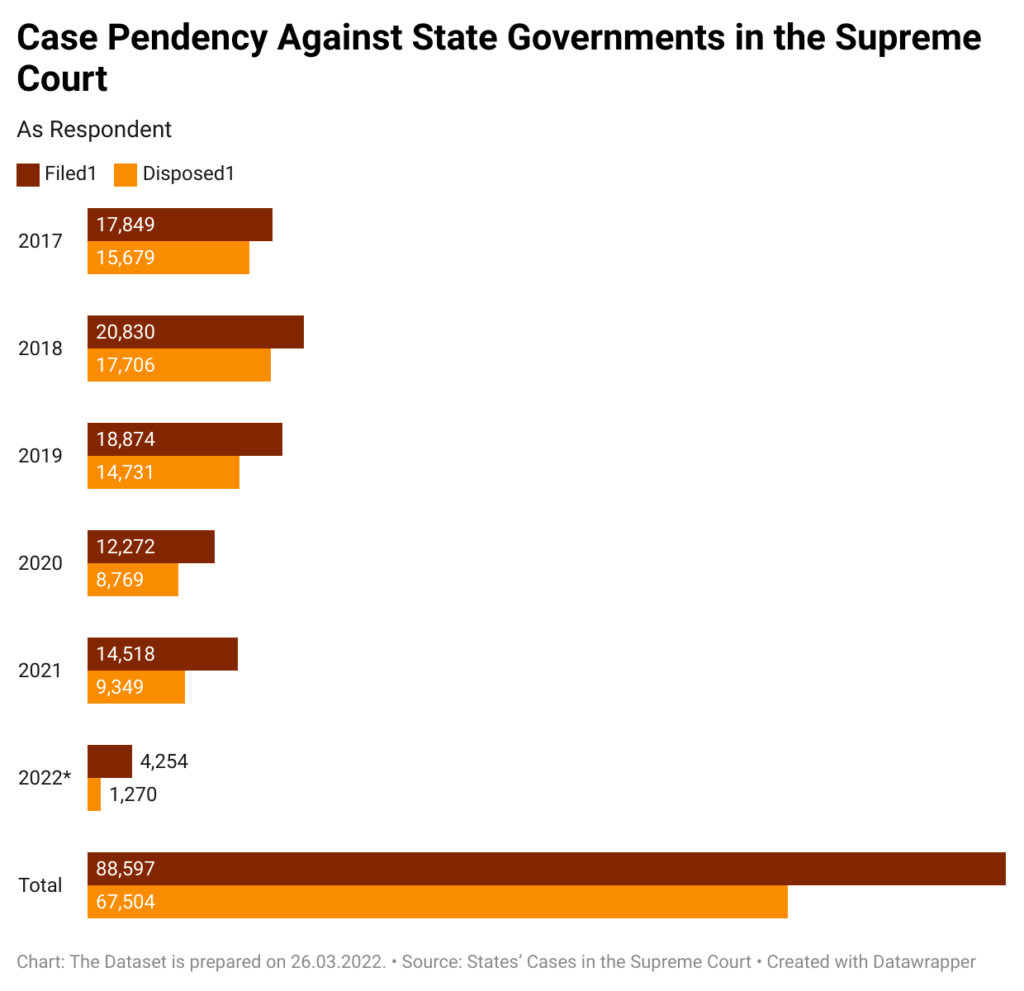

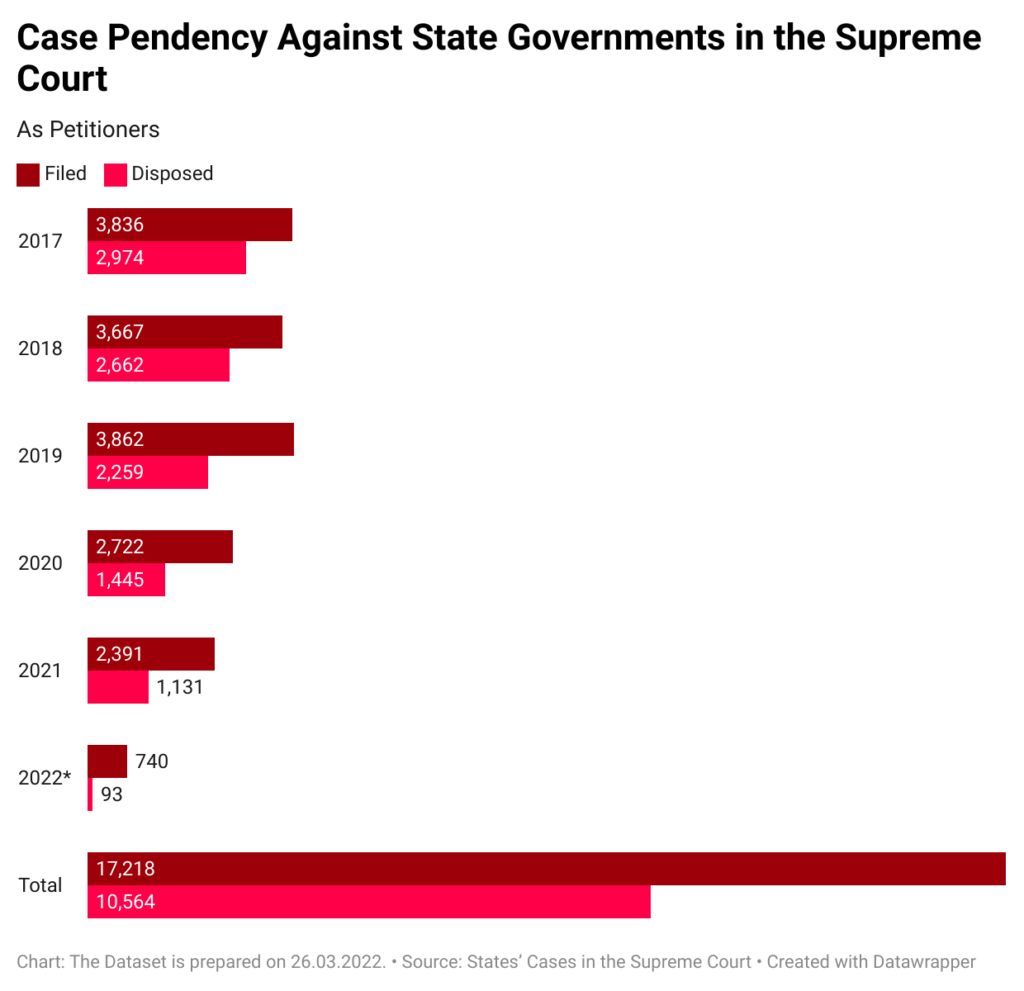

Similar to the NLP, understanding the workings of the SLPs requires studying their effectiveness in reducing the caseload and their implementation by the stakeholders. The process prompts us to analyse datasets related to case pendency in courts (at the state level). One must acknowledge that studying government litigation at this level entails practical difficulties for the researchers as it involves filtering the massive case data that are classified under different confusing case categories. For instance, the NJDG data provides a holistic overview of the different case types and their pendency at every tier of the government. Yet, it is difficult to ascertain from this data the specific number of cases where the state government is involved as a party.