I. The Big Idea: from Automation to Transformation

Judicial reform efforts globally have sought to improve efficiency, transparency, and access to justice through digitisation. However, technology alone cannot resolve structural bottlenecks embedded in fragmented, manual, or circular workflows. This is where process re-engineering becomes critical.

“Process re-engineering” refers to the fundamental re-thinking and re-design of court processes to achieve performance improvements, such as faster time to case disposal, better user experience, or more effective use of judicial time. It is not a question of automating existing forms and flows but questioning the necessity, sequence, and value of each procedural step. A shift from process replication to process transformation is central to sustainable judicial digitalisation.

Under process re-engineering, not all processes must be retained and those that cannot be reasonably streamlined, simplified, or automated may be outright eliminated.

II. What is a Judicial Process?

Judicial work comprises hundreds of processes: some of which are visible (such as filings, hearings, and orders) while others are largely hidden (such as scrutiny, preparation of daily schedules, or research and preparation done by judges). Processes lead to distinct services that are provided to litigants, lawyers, judges, court staff, and the public.

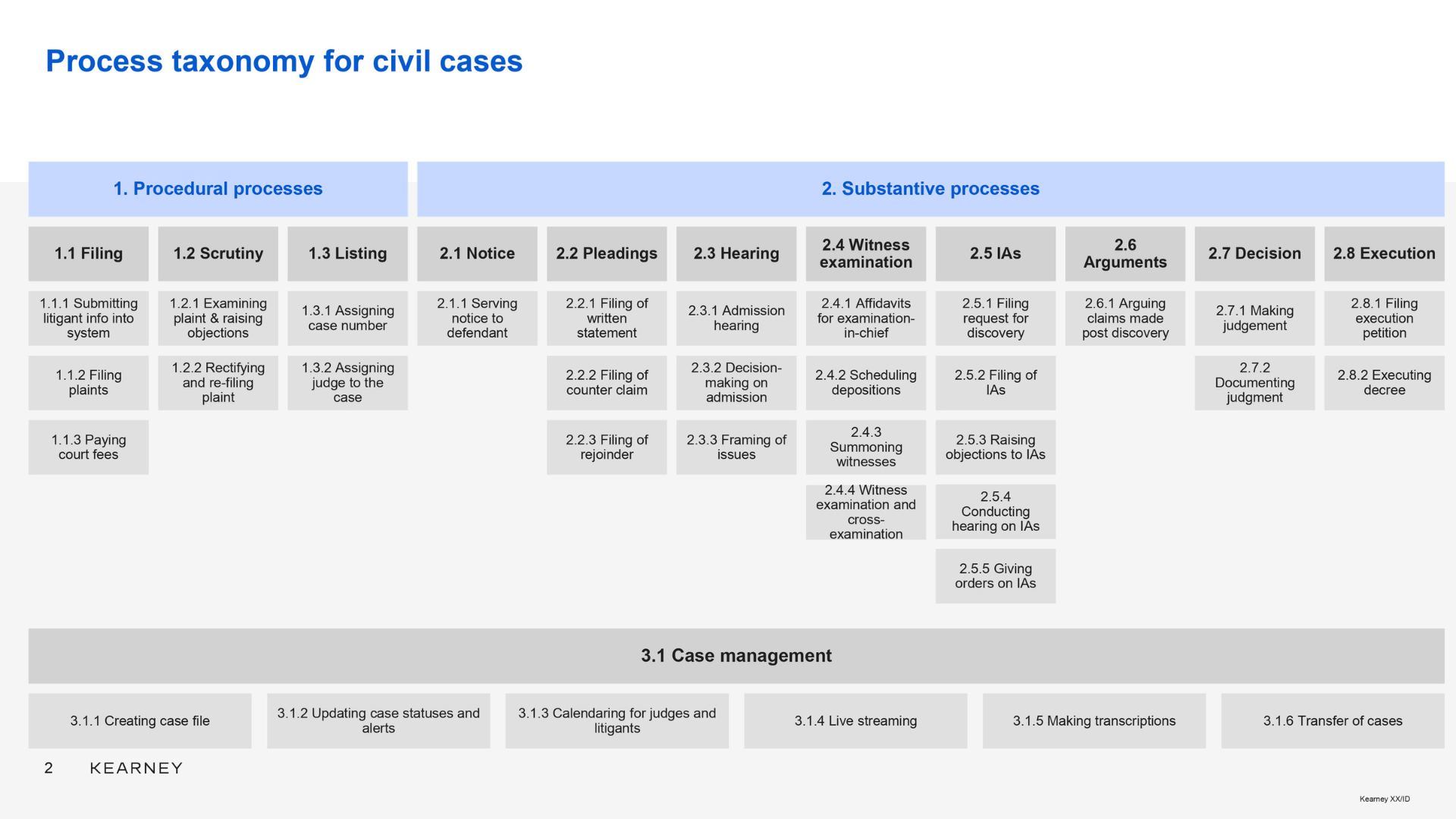

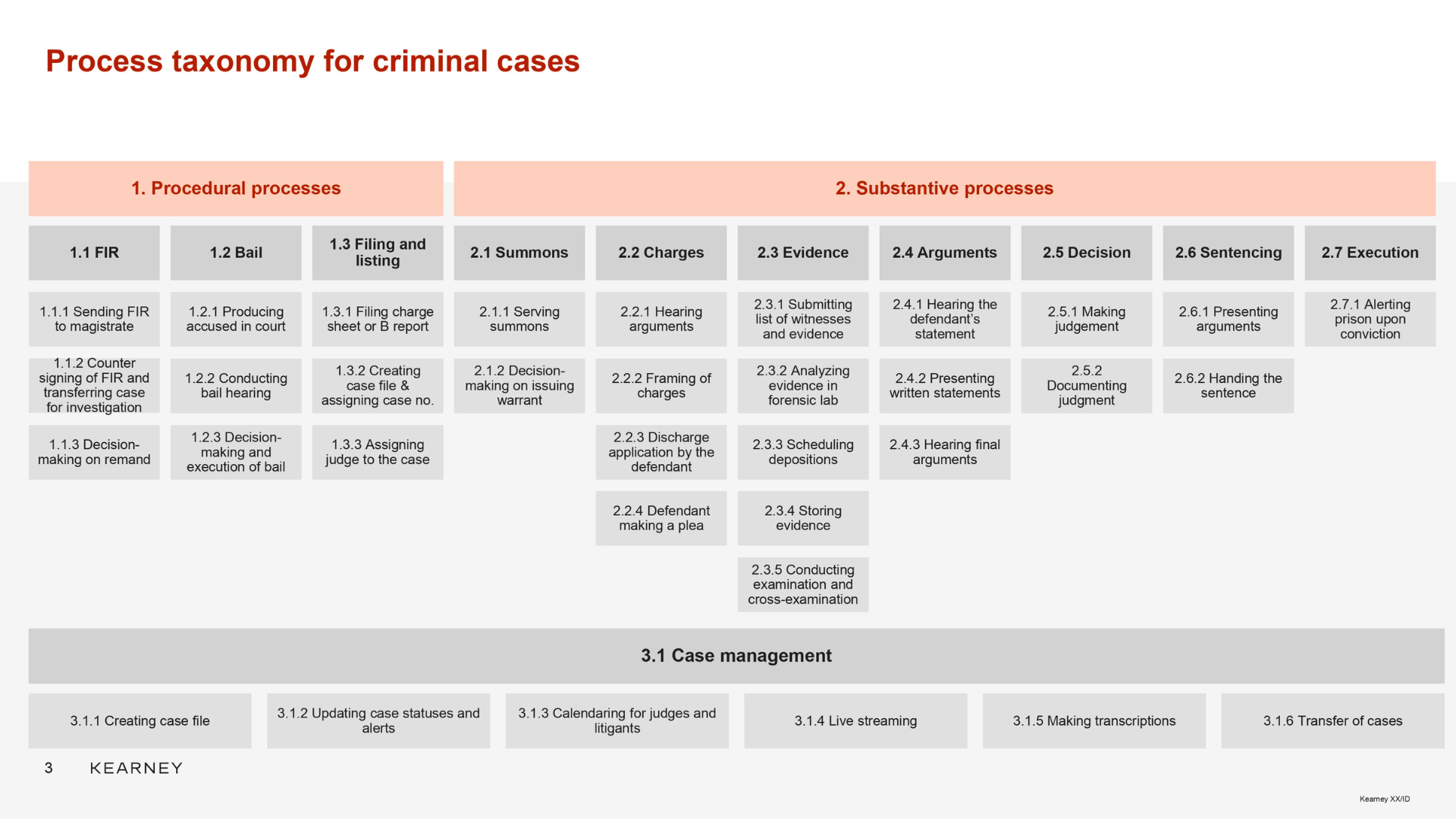

A taxonomy or structure is necessary to systematically map and analyse judicial processes; it may include the following dimensions:

| Dimension | Categories |

|---|---|

| Type of Case | Civil, Criminal, Commercial, Writ, etc. |

| Stage of Case | Filing, Pre-trial, Trial, Judgment, Execution, etc. |

| Process Type |

Procedural (ex: scrutiny), Substantive (ex: witness examination or evidence), Case management (ex: calendaring for judges and advocates) |

| Initiator | Judge, Advocate, Registry, System (ex: auto-listing) |

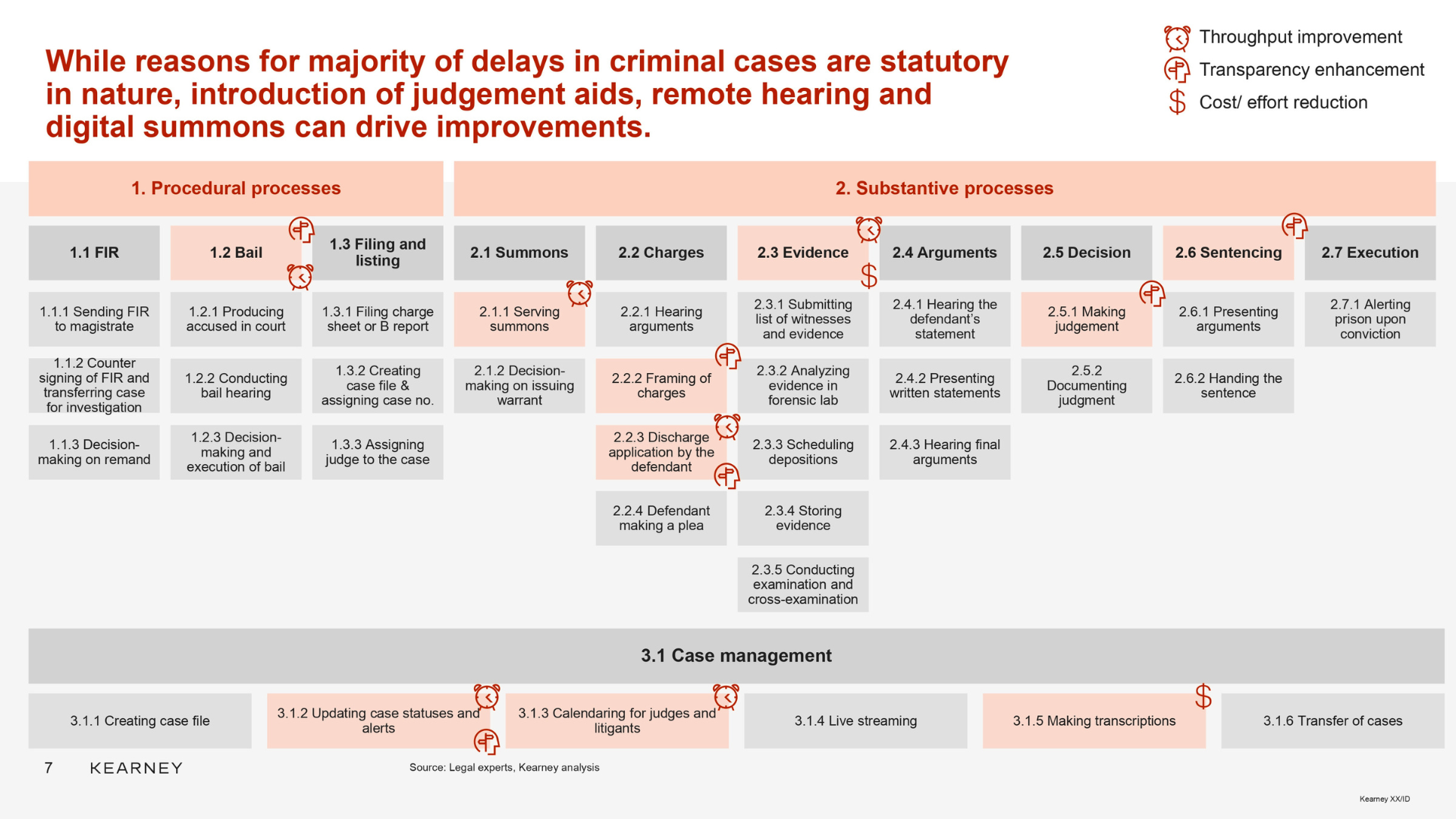

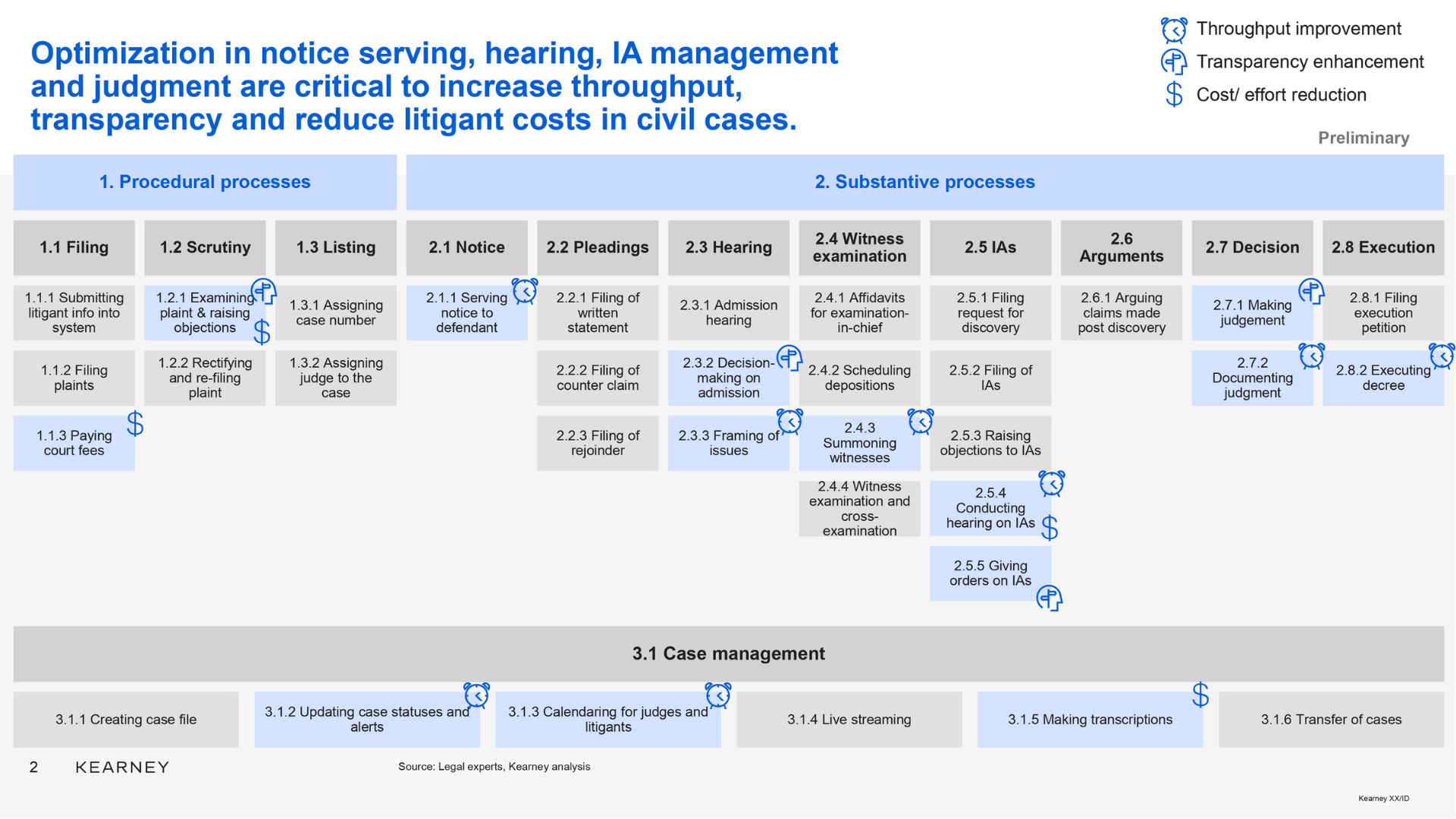

This classification allows institutions to group similar processes, identify high-turnover functions, and compare workloads across courts. Presented below are sample (simplified) taxonomies of judicial processes, prepared separately for courts with civil and criminal cases.

Each process has its own workflow, which is a series of discrete roles, tasks, documents, and checkpoints. To create a baseline of the current "as-is" process, further details may be required from stakeholders who know the system best.

A process detailing exercise can not only capture the current state, but also –

- (i) issues or challenges

- (ii) a vision of how the process may be improved

Moreover, there may be a gap between the process that was designed on paper and how it works in practice.

For example, e-filing is enabled in many courts and tribunals across India – however advocates report that they must submit paper documents as well. Some courts have begun conducting scrutiny using digital copies of petitions and creating digital trial bundles for further use of judges, but this is not yet widespread.

III. How to Conduct a Baseline Process Mapping Exercise

A process mapping exercise may be thought of as five iterative steps:

- Creating a process taxonomy: Create a comprehensive list of court processes within a selected jurisdiction or case type. This can be done by analysing documents such as rules, forms, practice directions, circulars, standing orders as well as interviews or Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with key personnel.

- Stakeholder validation: Engaging registry staff, judges, court managers, as well as the users, who may be litigants and advocates to validate the map to capture who does what, when, with which documents and decisions.

- Representing the workflows visually through a flowchart or process map that capture start and end points, decision nodes, parallel steps, and potential points of failure.

- Estimating time and resource measurement:as processes are digitised, it becomes easier to capture when case files are submitted or transferred between offices or how much time is spent on each hearing in a courtroom. While accurate measurement of time taken at each step, delays between steps, and human or technical resources consumed may not be currently possible, systems may be designed to inform future iterations of process mapping.

- Mapping pain points and risk identification: Through stakeholder reporting, courts can flag bottlenecks, duplication, inefficiencies, or discretion-heavy steps that cause delay or introduce opacity.

Presented below are some initial pain points and risks mapped onto our civil and criminal process taxonomies

IV. From Process Mapping to Gap Analysis

Once baseline mapping is complete, gap analysis identifies the shortfalls or issues between the current or as-is state and desired or to-be state. This may include:

- Rule-based Gaps: Are processes governed by obsolete or unclear rules?

- Capacity Gaps: Are key steps delayed due to staffing or skill shortages?

- Data Gaps: Are there key missing data points or metrics needed to monitor progress?

- User-Centric Gaps: Are advocate and litigant-facing steps overly complex or inaccessible?

Gap analysis helps prioritise which processes should be reformed first based on their impact, frequency, and feasibility.

V. Why This Matters: Making eCourts More Than a Digitisation Project

Process re-engineering defines whether digital infrastructure leads to digital transformation or dysfunction. Without well-imagined workflows, courts risk building IT systems that replicate or exacerbate existing inefficiencies: they may build case information systems with inaccurate or unusable data, scheduling systems disconnected from urgency norms, or dashboards that can measure volume but not bottlenecks. Process mapping enables the creation of a shared blueprint for case lifecycle management and a rational basis for platform design and policy reform. Further, the gap analysis creates objective criteria to prioritise and sequence which processes are in most urgent need of reform - whether through re-engineering or automation.

Moreover, courts today operate in an ecosystem of actors, such as prisons, police, prosecutors, legal aid, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) providers, etc., each of which operates as per its own workflows. Clearly defined processes are the first required to facilitate interoperability of digital systems across public institutions.

VI. Case Studies

Several Indian public sector initiatives provide useful examples for judicial process re-engineering:

- Passport Seva Project (Ministry of External Affairs): Redesigned backend processes with public-private partnership, achieving significant service improvements.

- Income Tax Department: Centralised processing of returns with a transparent, rules-based engine.

- GST Appellate Tribunals: As quasi-judicial forums being newly established, they present a rare opportunity to design an end-to-end dispute resolution process from the ground up that is efficient, user-sensitive, and natively digital.

VII. Further Resources

- How to Modernise the Working of Courts and Tribunals in India. NIPFP Working Paper Series (2019). Dutta, P., Hans, M., Mishra, M., Patnaik, I., Regy, P., Roy, S., Sapatnekar, S., Shah, A., Singh, A. and Sundaresan, S.

- Court Procedures and Process Reengineering: Need, Scope and Limits. National Judicial Academy (2017–18). Shivaraj S. Huchhanavar.

- Steps to Reengineering: Fundamental Rethinking for High-Performing Courts. National Association for Court Management [USA] (2012). Knox, P., Bleuenstein, C., Cornell, J., Griffith, S., Kiefer, P., Klaversma, L., Risi, T., Zastany, R., Harris, P., Slayton, D., Oken, M., Hess, S., Immediate, J., Bowling, K., Lewis, Y., Grant Brantley, H., Director, U., Billotte, R., Thomas, N. and Delaney, D.